Thoughts from 2014: Homeland security concerns stemming from the September 11, 2011 attacks on American soil, left our Nation’s legislators looking for improved methods to keep our communities safe from terrorists and drug traffickers. The Senate looked to newly-retired California highway patrolman, Joe David. In 1989, David created a training firm called Desert Snow in order to teach the stop-and-seize techniques he developed over a long career. Desert Snow’s method works similarly to drug interdiction efforts in the 1990s, but focuses on the cash instead. David’s idea was simple: cripple drug networks by taking cash without having to prove they committed a crime. But as law enforcement agencies speed to catch up with drug trafficking efforts in their respective jurisdictions, notions of due process disappear in the rearview.

In 2004, David expanded Desert Snow’s reach by creating a private network for police called Black Asphalt Electronic Networking & Notification System. The Networking system serves as a forum for law enforcement officers to share stories of their “hauls” of cash and drugs with each other. The network now hosts more than 25,000 individual members who have exchanged tens of thousands of reports detailing seizures from motorists, many of whom face no charges. Officers have listed a number of suspicious factors that typically lead to warrantless searches of passenger vehicles: dark window tinting; air fresheners or their smell; trash littering; inconsistent or unlikely travel story; a vehicle on a long trip that is clean or lacks baggage; a large number of energy drinks; a driver too talkative or too quiet; signs of nervousness (perhaps about the appropriate amount of talking necessary); inappropriate clothing or attire; and multiple cellphones.

Forfeiture

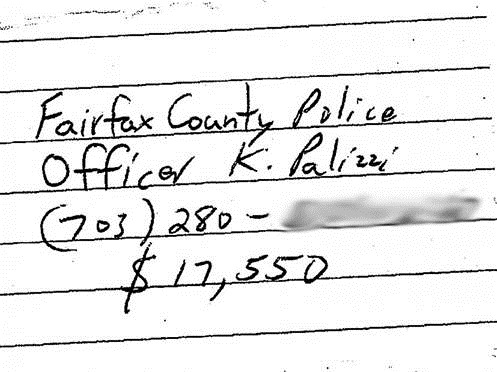

Under the federal Equitable Sharing Program, police have seized over $2.5 billion since 2001 from individuals that were not charged with a crime and were executed without a search warrant being issued. In the typical scenario, officers trained in the techniques of interdiction utilize one of the above-mentioned factors as a pretext to warrantless searches. Commonly, when no drugs can be found and large sums of cash are present, the motorist leaves the scene with nothing more than a paper receipt for the amount confiscated by law enforcement. The success of these methods is dependent on victims that are unaware of their rights and unable to afford subsequent legal services. Since 2000, officers in the Texas Panhandle have confiscated more than $12 million in currency alone, which is assumed to be drug related. Motorists who have their cash confiscated are, contrary to the bedrock principle of America’s judicial system, guilty until proven innocent. Take Mandrel Stuart, for instance. Stuart and his girlfriend were pulled over on Interstate 66 as they were travelling to the District of Columbia to purchase restaurant supplies. The officer’s reason for the stop: Stuart’s SUV had tinted windows and a video playing in sight of the driver. Stuart was handcuffed, detained without charges for over 2 hours, before being released with only a receipt for the $17,550 in cash—money earned by his Stanton, VA barbeque restaurant, Smoking Roosters—confiscated by Fairfax County Police. Fairfax County police spokesman, Don Gotthardt, calls police efforts, “effective tools–as long as they are properly used.” “There is absolutely the potential for misuse and abuse,” but people of Fairfax County, rest assured, “Fairfax County absolutely would not tolerate misuse and abuse.”

Recovery

Recovery is costly and often takes a substantial amount of time. Taking property without due process, or “policing for profit”, requires that motorists prove that they own the money and that it was earned by legitimate means. An alarmingly low number of these cases are challenged in court, as most often, the costs of litigation outweigh the benefit to be “[re]gained.” Mandrel Stuart was ultimately able to “win” his money back in Court; but at what cost? The entire process, from traffic stop to judgment, took a total of 14 months. Fortunately for Stuart, the Government had to foot his legal bill, which totaled close to $12,000.00, but he had to close the doors to his restaurant in the meantime.

You might be asking, “Where does the money go?” Well under the federal Equitable Sharing Program, state and local authorities share the proceeds with the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security, but retain a large portion. Essentially, there is an incentive for police to seize cash discovered in vehicles while issuing no citation, because then the motorist must initiate a civil recovery action. Whereas, when a citation is issued, or the motorist is arrested on any charge, the motorist will have her day in court and can dispute the seizure at that time. If you find yourself in a routine traffic stop, the key is to know your rights. During a routine traffic stop, an officer can: order all occupants out of the vehicle; perform a “patdown” of the driver or occupants, if there is reasonable suspicion to believe that they are armed or carrying drugs or contraband; ask questions relating to the occupant’s ultimate destination and purpose for the trip; ask questions relating to the ownership of and insurance covering the vehicle; and request permission (if no independent reason exists to conduct a statutorily authorized, warrantless search) to search the vehicle.[1]

The lesson to take away as you travel across the Big Country: whether you are given a citation or not, make sure to keep your receipt—it may be what helps you “recover” what is rightfully yours.

[1] List is non-exhaustive.